Archaeological Evidence of an Enslaved Home Space

by Ianna Recco, Collections Manager

Excavation area located on the north side of the property and east of the center walk. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, 2022.

In 2013 and 2022, archaeological excavations were undertaken on the grounds of Tudor Place to determine if a dwelling used by enslaved individuals once stood on the site. Architectural and domestic artifacts from a 2010 survey marked the Orchard as a potential point of interest. Subsequent excavation and analysis in the area supported the conjecture that a building likely stood on the site due to the presence of ceramics, food remains, personal objects and a probable root cellar. Certain artifacts and architectural features consistent with surveys of other enslaved home spaces in the region suggest that enslaved individuals lived in and used the space. Ceramicware analysis indicates that the structure stood from the first half of the 19th century until shortly after the Civil War.

It was likely a timber-framed brick building that served as a multi-use workspace and home space. Abutting the central driveway of Tudor Place, its placement and proximity to the Peter family’s house would have been advantageous to them to exercise constant surveillance. The archaeological record suggests the building was abandoned shortly after the Civil War, demolished and erased from the memory of the Tudor Place landscape like thousands of other enslaved dwellings in the region.

These structures were built on foundations of bondage and oppression while at the same time, were homes where culture, community and family bonds persevered. Although they were constantly under the gaze of the Peter family, these were spaces where enslaved people defiantly fostered a sense of community. In her analysis of enslaved home spaces, archaeologist Whitney Battle-Baptiste incorporates bell hooks’s concept of homeplace to determine that “the lives of enslaved Africans were structured by racism, sexism, and oppression. As such, the solace of a place called home takes on an added dimension for the daughters and sons of slavery. It provided a place to regroup, to find the strength to resist.”[1]

On the enduring significance of these spaces, Battle-Baptiste writes that they were “the epicenter of Black cultural production.”[2] Archaeological evidence at Tudor Place suggests that enslaved individuals exercised their agency in these spaces with culturally significant activities like cooking, dining, gardening and recreation. The variety of ceramic fragments archaeologists uncovered indicates that food was central to activities in the space. Numerous terracotta flowerpot fragments were found suggesting that people were either gardening to supplement their diets or were raising plants for the garden at Tudor Place.

They were likely using stoneware and earthenware vessels for food storage and preparation. Archaeologists found a fragment of low-fired, locally produced earthenware and tentatively identified it as Colonoware, a style of unglazed ceramicware frequently created by Black artists using ancestral African methods.[3] Oyster shells, butchered bone fragments and fish scales were identified, revealing clues about cuisine. Archaeobotanical analysis also determined the presence of a carbonized Amaranthus seed, a valued food plant in many African and diasporic communities. From growing seedlings to serving meals, the archaeological evidence shows that these individuals invested time and care in their diets.

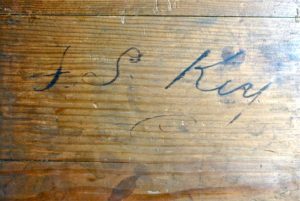

Among the personal objects excavated were a pipe and toothbrush fragment, small testaments of someone’s daily habits and routines.

Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, 2022.

Whereas food-related artifacts tell us about the community practices of enslaved people, personal objects unearthed can tell us more about the people as individuals. Several intimate artifacts were discovered in what may be a dug cellar or subfloor pit, a feature commonly found in association with enslaved dwellings. In an analysis of subfloor pits in Virginia, archaeologist Patricia Samford hypothesizes that they were a shared cultural practice to store food and personal or valuable items and that some were potential shrine spaces that evoked ancestral West African religious practices. Among the artifact assemblage in the pit, archaeologists discovered a blue-green bead, an object commonly found at sites of enslavement that scholars believe may have represented a collective belief system and practice. Enslaved individuals often wore glass beads, especially blue and green ones, as a form of self-adornment and potentially as charms to protect and promote wellbeing.

Fragments of containers and flowerpots demonstrate how people thoughtfully prepared for the future by storing food and cultivating plants in this location. Dovetail Cultural Resource Group, 2022.

In addition, archaeologists uncovered two clay smoking pipe bowls, one of which features a molded crown design. From these objects, we can glean what people may have worn to express their individuality and what recreational activities they partook in when they had a moment to themselves. Although this home space was demolished and forgotten long ago, the stories contained within it and the greater landscape of Tudor Place continue to unfold as the legacy of its enslaved community persists.

[1] Whitney Battle-Baptiste, ““In This Here Place”: Interpreting Enslaved Homeplaces,” in Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora, ed. Akinwumi Ogundiran and Toyin Falola (Bloomington: Indiana University, 2007), 235. For bell hooks’s conceptualization of homeplace, see bell hooks, “Homeplace (a site of resistance),” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Boston: South End, 1990), 41-49.

[2] Battle Baptiste, “In this Here Place,” 233.

[3] To learn more about Colonoware, see the Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery at https://www.daacs.org/galleries/colonoware/.

Sources

Battle-Baptiste, Whitney. “In This Here Place”: Interpreting Enslaved Homeplaces.” In Archaeology of Atlantic Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Akinwumi Ogundiran and Toyin Falola, 233-248. Bloomington: Indiana University, 2007.

Lee, Lori. “Beads, Coins, and Charms at a Poplar Forest Slave Cabin (1833-1858).” Northeast Historical Archaeology 40.1 (2011).

Pogue, Dennis & Sanford, Douglas. Housing for the Enslaved in Virginia. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-housing-in-virginia.

Samford, Patricia. Subfloor pits and the archaeology of slavery in Colonial Virginia. University of Alabama Press, 2007.

To download this article, click here: