Up in Arms: A Family’s Service

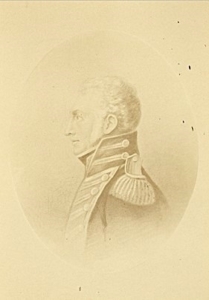

Portrait of G. Washington Peter c.1810-1820 Engraving (Tudor Place Archive)

TUDOR PLACE TIMES | SUMMER 2024

From the early days of the United States of America through the Korean War, the Peter family proudly served in the armed forces. Through these 150 years, sons, and later daughters, were guided by a strong familial connection and an overall sense of patriotism to serve their country. These military stories are kept alive by the objects they left behind, preserved by later generations of the family.

From the early days of the United States of America through the Korean War, the Peter family proudly served in the armed forces. Through these 150 years, sons, and later daughters, were guided by a strong familial connection and an overall sense of patriotism to serve their country. These military stories are kept alive by the objects they left behind, preserved by later generations of the family.

The Beginning: Major G. Washington Peter

G. Washington Peter, born 1779, was the younger brother of Tudor Place’s first owner, Thomas Peter. Early in his life, he had a desire to join the military, running off at just 15 years old to try to join the Maryland troops and help defeat the Whiskey Rebellion. Though

he was sent home by George Washington from the Whiskey Rebellion, it would be through Washington’s recommendation that Washington Peter received his first commission to 2nd Lieutenant in the United States Army from President John Adams. While there seems to be no trace of this commission, his later commission to Captain from Thomas Jefferson is well preserved and complements his later letters while he was serving as the commanding officer at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, where he set up the first light artillery unit in the country. After leaving Fort McHenry, he later resigned his commission to protest the sale of his unit’s horses, but his drive for service never stopped. He organized a unit of the Georgetown Militia which was one of very few units to return fire with the British at the Battle of Bladensburg on August 14, 1814 before their march on Washington(1). Though his military service came to a close, George Peter held onto a seating chart from the 19th Congress where he served as a representative from Maryland where he worked alongside prominent future leaders including Sam Houston, James Buchanan and James Polk(2).

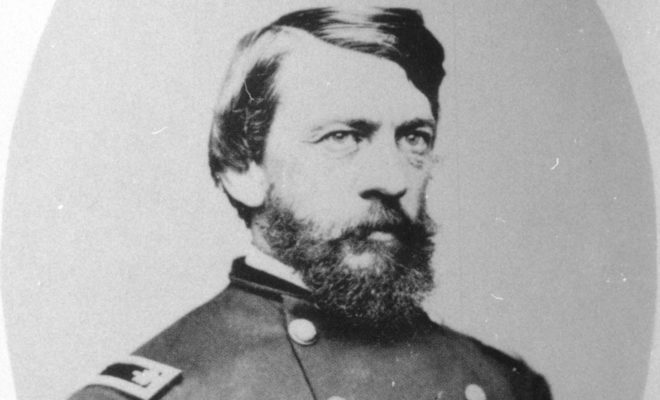

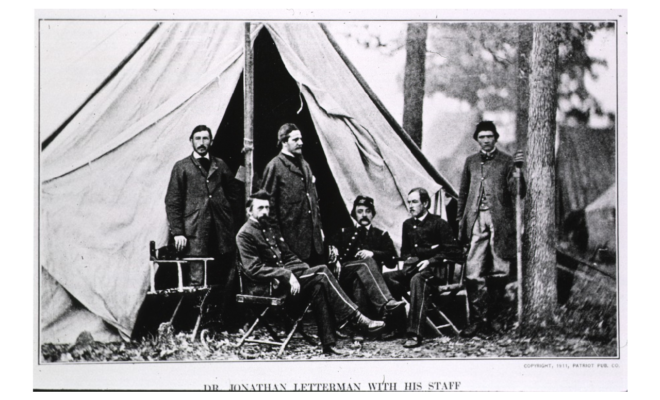

Family Tragedy: Captain William G. Williams

Captain William G. Williams found love with America P. Peter, one of the daughters of Thomas and Martha Peter right after he graduated from the Military Academy at West Point in 1824. From there he was assigned as a Topographical Engineer in Buffalo, New York. At the start of the Mexican American War in April 1846, William Williams was under the command of General Zachary Taylor whose unit was brought to Mexico. In September 1846, Taylor’s unit, including Captain Williams, was in Monterrey, Mexico. On September 21, Captain Williams was sent on reconnaissance mission and found himself in an unfortunate position when the Mexican troops started firing from Fort Teneria. General Braxton Bragg explained the story of Captain Williams’ death in a letter that included a map to Captain Williams’ son Laurence Abert Williams in 1854. He wrote in high regard of the Captain at the end of the letter saying “most nobly did he meet his fate, forgetting himself and his suffering when the cause required”(3). Accompanied by his sword, portrait and buttons from his Topographical Engineer Uniform the story of a man who gave his life for the United States at 45 years old resonated and was preserved through the family line.

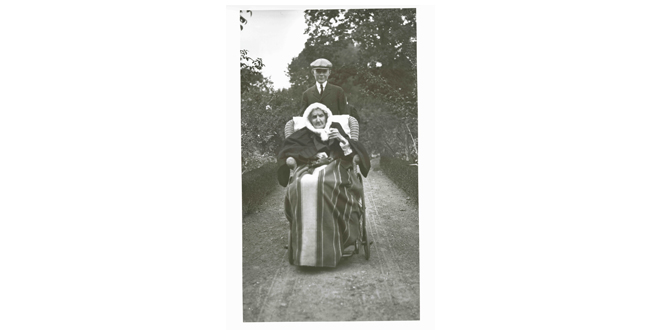

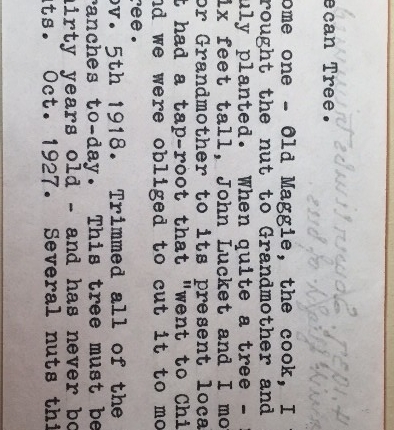

Women in the War: Agnes Peter and Caroline Peter

In World War I and II, women were not able to serve on the front lines, but many women found ways to contribute to the war effort on the home front. Agnes Peter, Armistead Peter Jr.’s sister, enrolled in a boarding school in Tarrytown, New York which taught her skills like typing, driving and automobile repair. When the program concluded in summer 1918, Agnes was ready to travel to Europe to put her skills to use, but by the time her paperwork arrived, the Armistice had been signed. Yet, Europe still needed help after the war. Since she had all of her paperwork, Agnes traveled to France under the YMCA and helped people and communities there until 1921. Agnes’ passport with its cancellation stamped in 1921 shows her dedication to the work she was doing alongside the ribbons and honors she received for her humanitarian work in France(4). It was women who provided crucial humanitarian work to help countries and families rebuild following the turmoil of war. Agnes might not have been a soldier, but her wartime dedication and passion followed her family legacy of service. Caroline Peter, wife of Tudor Place’s final owner, Armistead Peter 3rd, served in a similar role as a nurse for the American Red Cross during both World War I and World War II(5). She served in these roles at the same time her husband, Armistead Peter 3rd, was serving in the U.S. Navy. As the last private owners of Tudor Place, Caroline and Armistead continued the family legacy of patriotism and service as they both served during those wars. The Peter family, over more than a century, proudly embraced military service and a deep love for their country that was preserved through generations.

– Alex Brandis, Spring 2024 Collections Intern

Source List:

1. MS-4 Finding Aid; Major George Peter Biographical Sketch

2. House of Representatives Seating Map, 19th Congress by A.J. Stansbury 1825 (MS4, Box 3,

Folder 22, Document 3)

3. Braxton Bragg to Laurence Albert Williams Describing the Battle of Monterey, September 24,

1954 (MS12, Box 1, Folder 7)

4. Agnes Peter’s World War I United States Passport, 1918

5. MS-22 Finding Aid; Caroline Ogden-Jones Peter Biographical Sketch