As a granddaughter and namesake of Martha Washington, Tudor Place founder Martha Parke Custis Peter inherited several important pieces of her correspondence following the death of the first president.

Since 2015, the University of Virginia has been annotating and publishing the Mrs. Washington’s letters as part of an ongoing partnership between The Washington Papers project (formerly the Papers of George Washington) and the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon. Inspired by this project, Tudor Place Archivist Wendy Kail has added to the record by studying her letters and draft replies at Tudor Place and related documents in other archives for what they reveal about the Washingtons’ marriage, deaths, and legacies. Kail’s richly researched essay is presented here in three parts.

ABOUT THE SLIDESHOW:

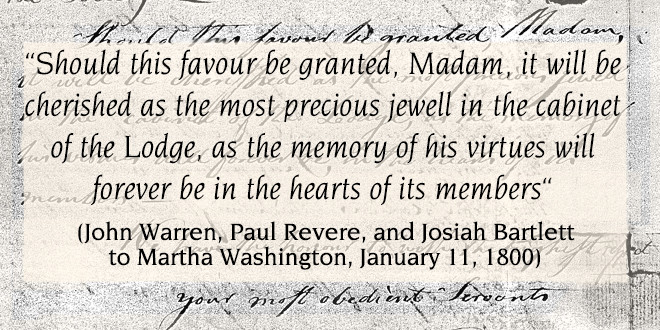

- Detail of letter from Massachusetts patriots requesting lock of Washington’s hair. Collection of Tudor Place Historic House & Garden Archive

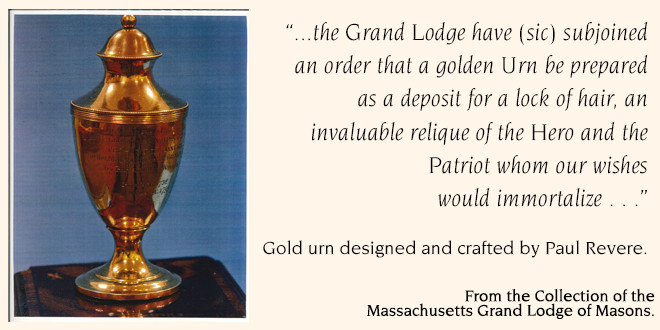

- Gold urn crafted by Paul Revere as repository for the lock of George Washington’s hair given by Martha Washington. Collection of Grand Masonic Lodge of Massachusetts

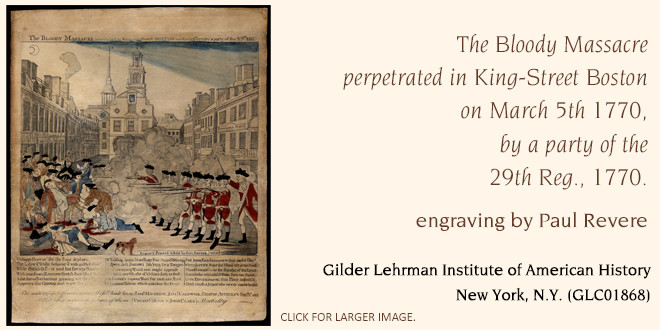

- Two engravings by Paul Revere demonstrating his support for the Patriot cause, devotion that later inspired his role in the Massachusetts Masons’ memorialization of George Washington. Collections of Gilder-Lehrman Institute.

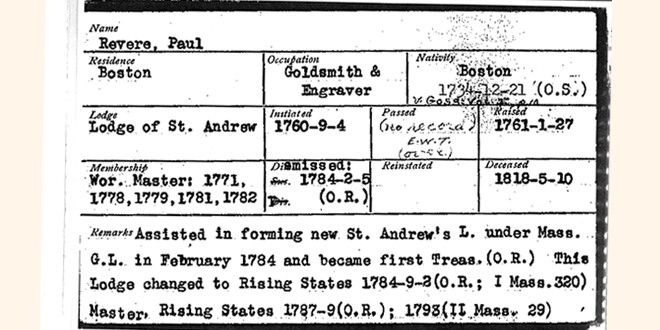

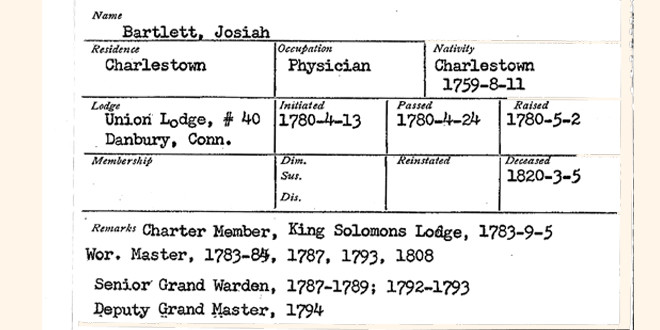

- Revere’s and Warren’s Masonic membership records. Collection of Grand Masonic Lodge of Massachusetts

The death of George Washington was a stunning loss to his country as well as his family. At Mount Vernon, Martha Washington enlisted Secretary Tobias Lear’s help fielding voluminous letters of condolence, tributes, and requests for memorial locks of the President’s hair. Granddaughter Martha Parke Custis Peter inherited some of this correspondence, including Lear’s drafts, and they remain in the Tudor Place Archive. In Part One of the Washington Letters essay, Archivist Wendy Kail delves into records from Martha’s widowhood to divine what Washington meant to his countrymen.

The essay’s second part, “Legal Aid,” reviews profuse discussions of the wills of both Washingtons, following George’s death in 1799 and Martha’s in 1802. Their estates were orderly, with respected (male) relations as executors, but complicated, and hint at family ties and affections but also possible rivalries. The questions that arose concerning both legacies offer a “case study” of not just the big questions that follow a prominent demise but the numerous quotidian details: Who owned the right to harvest and who must pay for the seed for crops on an inherited farm? Would the executors honor Mrs. Washington’s verbal promise to her granddaughters of Sèvres china? And who owned a pair of mirrors plastered to Mount Vernon’s walls?

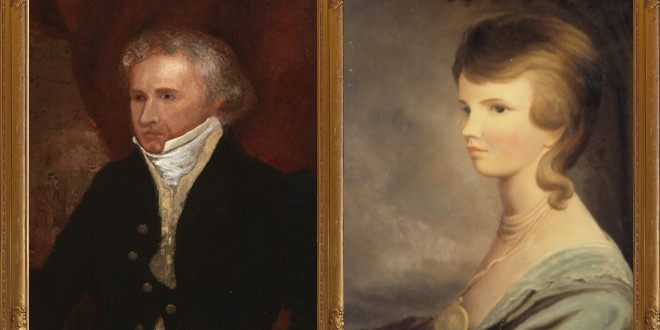

The essay’s third and final section, “A Tug of War,” examines one America’s rarest early documents – a letter from George to Martha Washington. In the Tudor Place Archive, it’s one of just three pieces of their personal correspondence in existence. Washington wrote it upon accepting command of the Continental Army, offering a rare if subtle glimpse of the affection between this notably reticent couple. As Kail notes, the general’s almost apologetic argument for service “foreshadows the struggle they both would endure for the next seven years, literally a tug of war between duty and domicile.”

Each essay section contains footnotes, and a Bibliography comprises essay Part Four.

« Return to Topic

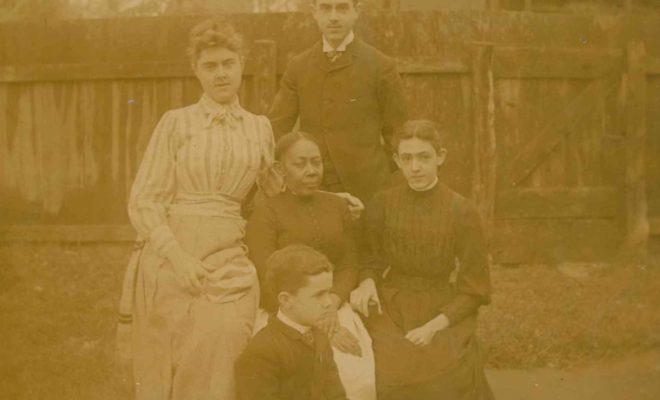

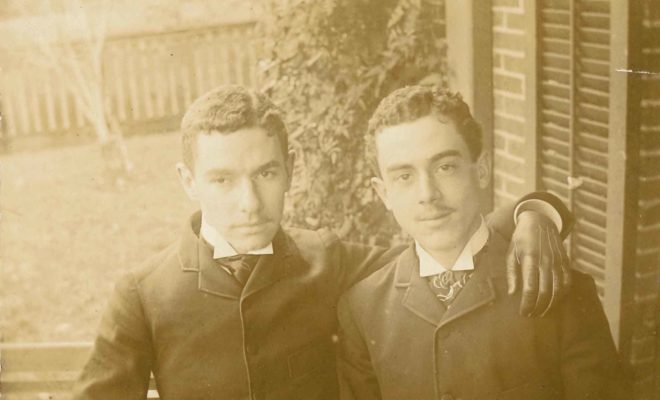

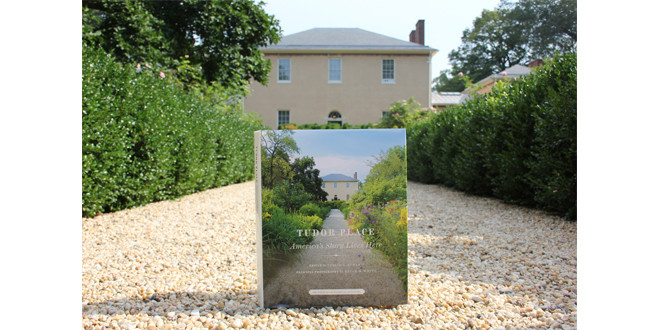

New discoveries are common at Tudor Place. Whether found in the back of a drawer, the bottom of a trunk, beneath the ground, or amid a box of family papers, encounters with “new” objects and information fuel the imagination and reveal fresh stories about the past. Tudor Place Archivist Wendy Kail’s 2019 discovery of an unattributed manuscript launched an inquiry that combined her skills as a historian, researcher, and sleuth to reveal the author of the work, as well as details of his life and a curious connection to Tudor Place.

New discoveries are common at Tudor Place. Whether found in the back of a drawer, the bottom of a trunk, beneath the ground, or amid a box of family papers, encounters with “new” objects and information fuel the imagination and reveal fresh stories about the past. Tudor Place Archivist Wendy Kail’s 2019 discovery of an unattributed manuscript launched an inquiry that combined her skills as a historian, researcher, and sleuth to reveal the author of the work, as well as details of his life and a curious connection to Tudor Place.