From the January Clean: An Unexpected Repair

Cleaning, counting, and assessing conditions are all part of the drill when the museum closes each year for what we call the “January Clean.” Rugs are rolled up, paintings removed from walls for examination, and the walls themselves examined. In the garden, bricks are relaid and trees trimmed amid the usual plant care and preparations for spring. The Museum Shop undergoes a careful inventory (14,000 postcards!), while in offices and workspaces elsewhere on the property, closets and cabinets are straightened, files sorted, and other year-long accumulations dealt with.

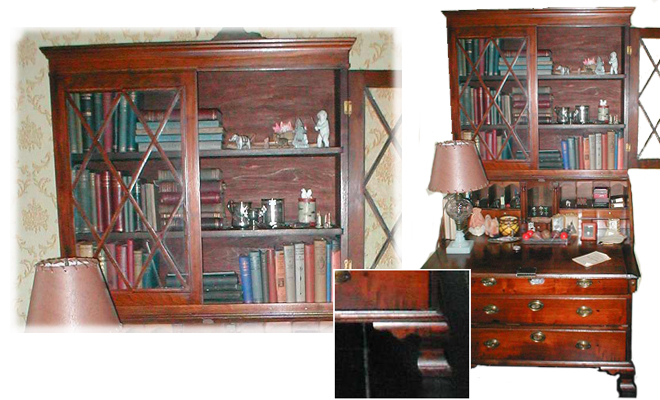

For collections staff especially, close examinations of objects left quietly undisturbed the other 11 months of the year leads sometimes to unexpected new projects. The repair of a heavy walnut desk bookcase in the North, or “children’s,” bedroom was one such. Armistead Peter 3rd, the estate’s last private owner, first brought the 19th century piece here from the family’s Content Farm, a Washington County, New York, property where they spent several months each year. Today, the desk bookcase holds school books, novels, small toys, and other objects from “AP3’s” childhood.

The desk bookcase is actually two separate pieces, an upper cabinet with two glazed doors that sits upon a desk with drawers and a fall-board writing surface. When they examined it as part of a routine January inspection, Curator Grant Quertermous and Collections Manager Kris Barrow found one of its rear feet had loosened too much to support the piece’s weight. To relieve the immediate pressure, staff removed the item’s entire contents and the upper case.

As so often happens with a “lived-in” collection like ours, long in use, Grant and Kris needed first to address an earlier repair. The leg had had been reglued during the mid-1900s, and the adhesive from this earlier repair had weakened over time. The leg and glue block (itself replaced sometime in the 20th century) had separated from their attachment point at the desk’s back corner, placing additional stress on the carved bracket foot.

The term “glue block” might be unfamiliar unless you collect or study antique furniture: It describes a small piece of wood that braces a corner joint — on this piece, where the two sides of the ogee bracket foot are joined. A piece like this desk bookcase, where the carved bracket foot is simply decorative, actually rests in back on two uncarved, square feet concealed behind the rear ogee bracket feet. With this rear foot loose and the joint separated from the glue block, much of the piece’s weight was now on the non-supporting decorative element, rather than the intended weight-bearing element.

Had we not detected the loose foot, the bracket foot could have split or, worse, buckled under the weight of the desk bookcase and its contents. Fortunately, the necessary repairs were uncomplicated. Staff elevated the desk on its back on padded saw horses to relieve the bracket and gain access to the damaged area and applied wood glue in key spots to re-attach the foot and glue block. Clamps were placed on the foot overnight to apply pressure while the glue dried. All of the work was documented and photographed as this repair now becomes a part of the physical record of the desk bookcase and is noted in its file. The piece itself, meanwhile, once stabilized, resumed its place along the wall and its familiar toys, books. and childhood treasures returned to its welcoming shelves.

Just one project among many, the exercise shows how the room-by-room January Clean enables us not just to monitor objects and spaces within the house but to undertake crucial conservation work where needed. For more complicated repairs and conservation, the January assessment often marks the starting point for extensive planning and, often, fundraising, for projects involving conservation specialists. [Tudor Place members are invited each January for a New Year’s breakfast and behind-the-scenes look at the January Clean and projects underway, scheduled this year on January 23, 2016.]

Having completed the upstairs rooms during the first week of January, Collections staff have turned their attention to the Drawing Room and Parlour, including careful cleaning of chandeliers (see the video clip) to make their crystals gleam. The Office, Kitchen and servants’ spaces follow toward the end of the month. Lastly, Grant will oversee the Dining Room installation for Presidents’ Day and spring’s highlighting of the Washington Collection, for which we happily welcome back the public when we reopen (at half price all month) on February 2, 2016.

View January Clean albums on Facebook: