Restoration of the Gazebo and Arbors

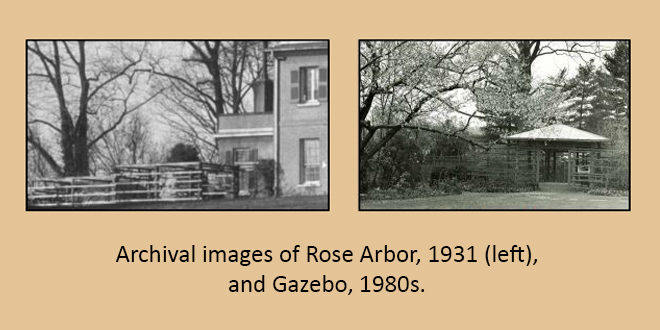

As part of its Master Preservation Plan, Tudor Place recently completed restoration of the wooden gazebo and arbors to the west of the main house. The service yard and its significant structures have served a variety of uses since the late 1700s. And the Asian-inspired gazebo built in the 1960s has provided a serene garden retreat for residents, and now the public, ever since. The October 2017 restoration and archaeological investigations that preceded it not only preserve them for a third century but enrich interpretation and scholarship surrounding them.

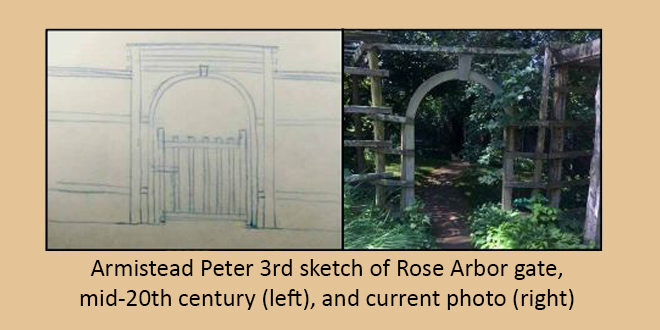

For more than a century, the area was a domestic service yard, hosting a kitchen, well and smokehouse. The kitchen and well were replaced in 1876 by construction of the attached kitchen a few paces away. The smokehouse — one of the District’s oldest known dependencies, or outbuildings — remained in place but was turned to contemporary uses that illustrate the changing nature of urban life over time. As Georgetown’s rural surroundings retreated, the Peters likewise migrated away from farm activities like smoking their own meat, leaving the smokehouse available for new ends. In 1927, when Armistead Peter Jr. converted it into a coop to raise squab, or culinary pigeons, he had an adjoining arbor built as an outdoor pigeon fly. In 1953, the smokehouse and attached arbor became a kennel for the family’s beloved English Spring Spaniels.

The west garden’s arbors also met decorative and recreational purposes. Rose arbors have graced that side of the main house since the earliest known photographs of the house were taken, in the 1860s. In the mid-20th century, Armistead Peter 3rd extended the structure, adding a graceful archway connecting the arbor to the pigeon fly. Around 1962, he designed the gazebo as a place to host luncheons and cocktail parties with his wife, Caroline.

The restoration replaced wooden elements of the gazebo damaged over the years by weather and the activity of carpenter bees and squirrels. The smokehouse arbor has been restored to its appearance during the pigeon fly era, with opportunities for new interpretive themes to share with visitors.

Before disturbing the soil for the restoration, Tudor Place engaged long-time partner Dovetail Cultural Resources for archaeological exploration of the area beneath. The findings yield a better understanding of the changing uses of this area over time, uncovering a range of artifacts including an 1898 Indian Head penny, clay marbles, fragments of a clay smoking pipe from about 1820, and a mid-19th century glass button. Part of a glass syringe was a reminder of the medical practice run from the west wing by Armistead Peter, Britannia Kennon’s son-in-law (and husband of Markie).

A generous financial commitment from a Tudor Place Board member underwrote the Smokehouse Arbor Restoration. Named gift opportunities remain available to support other aspects of the restoration work.

View vintage film footage of the pigeon fly: