by Director of Education Talia Mosconi

|

Cool River, Hot City: View of the DC-Georgetown Ferry

(rear left, loaded with wagons), and Aqueduct Bridge.

1862 stereograph by George N. Barnard. |

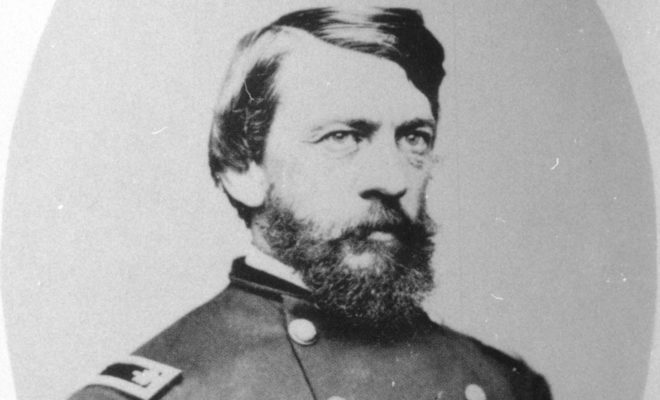

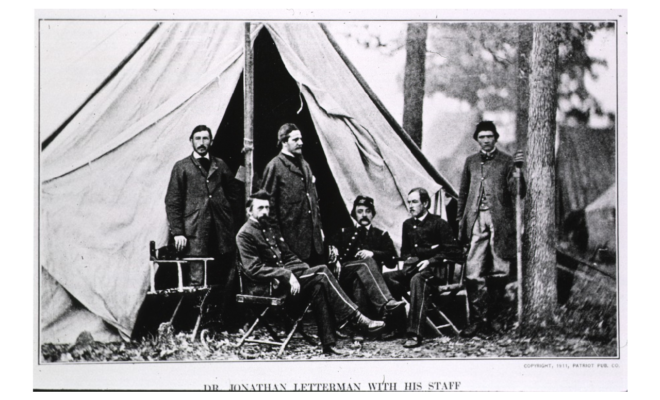

The region saw record temperatures for the just marked 150th anniversary of the Civil War’s first big battle, at Bull Run creek near Manassas. Our sagas and commemorations naturally focus on major battlefields. When we think of civilian travails, we tend to recall ravaged southern cities like like Richmond, Atlanta and Vicksburg. But with the surprise Union debacle at Bull Run, the conflict embroiled the District of Columbia before it reached these other homefronts. The hot summer of 1861 changed forever the city of Washington, the contiguous area north of Florida Avenue then known as “the country” and, of course, the village of Georgetown.

As demoralized Federal soldiers poured back from Bull Run, flooding Washington’s streets and public spaces, their return sparked panic about an impending Confederate onslaught. The Rebs never came, but President Lincoln’s call-up of 75,000 Union troops, all needing lodging, did lead to an “invasion” of sorts, as tent encampments sprang up, the government expanded into ever larger quarters, and a “beltway” of military forts was erected around the city. On residential city blocks and nearby farms, meanwhile, neighbor turned from neighbor, according to where their loyalties lay.

|

View of the C&O Canal running past Georgetown,

which retained an independent (sometimes divided) government until after the Civil War. |

In Georgetown, the reality of war quieted most pro-Southern voices. Residents often wondered which neighbors they could trust. The village and its port had been absorbed into the newly formed District of Columbia in 1790, but retained an independent government until after the war. Georgetown’s mayor and town dignitaries officially pledged fealty to the Union at the Recorder of Deeds or the Department of Justice. But perhaps as many as a quarter of local residents– including the mistress of Tudor Place — registered their loyalties another way, packing their bags and moving south. Others fled to Baltimore or Philadelphia to escape harm’s way. And Georgetown College—now University—was almost literally divided: Half its students returned to the South and the remainder went North, giving rise to the school’s lasting color scheme of blue (for Union) and gray (for the Confederacy).

|

Young people visit the Gap store there, now, but

once thronged Forrest Hall to enlist for the Union. |

Those who left expected to return in just a few weeks, after hostilities ended. The minister at Christ Episcopal Church (31st and O Streets), a slave owner from North Carolina, headed south, leaving his cat with ten days’ food. Its skeleton was later found by neighbors. Sons of loyalist families clamored to sign up for the Union at Forrest Hall (where the Gap store is, now) for three-month tours, the war’s expected duration. Other young men crossed the river to enlist in the Confederacy.

Some senior federal employees left Georgetown to offer their skills to the newly forming Confederate government. Leaders of long-standing militias left town quietly to join their troops, while other prominent families, despite owning slaves, stayed loyal to the Union. Still other local families found themselves, like many around the country, divided in their loyalties.

There was even a small “civil war” within Georgetown itself. The town’s governance consisted of four wards. One of these “seceded” from the rest, declaring independence with a manifesto consisting of just one word: “Dixie.” Pro-south arsonists repeatedly incited trouble, unsuccessfully attacking the mayor’s office, the Union Hotel, lumber yards, and part of the Rock Creek Bridge that connected Georgetown to the City of Washington. A 9:30 p.m. curfew was imposed, saloons were shut down, and Georgetown’s lone, horse-drawn, fire engine was put on 24-hour alert.

Re-enactors may have sweltered through the Bull Run commemorations last month, but the “heat” was even more intense 150 years ago, when the Capital City and Georgetown village emerged as hotbed and homefront for a searing national cataclysm.

Join us to learn about the Georgetown homefront on our exciting Civil War House & Walking Tours: Offered monthly through November 2011 on second Saturdays, the program includes guided walks through our mansion and surrounding streets. (Choose one or both.) Learn how Tudor Place reluctantly served as a boarding house for Union officers. Standing on other sites where history happened, hear about hospitals, spies, slaves and freedmen, and heartbreakingly divided families. The next tour, last of the summer, is August 13, so sign up soon!