Tudor Place Artist-in-Residence Peter Waddell is a history and architectural painter who has created major works with the White House Historical Association, Mount Vernon, the U.S. Capitol and other sites. For Tudor Place, he has created images that depict the house, gardens, and history of the site. This post — and its slideshow — will be updated as Peter makes further changes to his painting of the original Tudor Place wings.

My work frequently starts with someone needing an image of a place in history, usually where no images exist. Sometimes I am asked to record an existing building or interior because of a need for a permanent and minutely detailed record that also reveals the deeper meaning of the subject. Others start with an interest in painting an interesting place at a specific time in the past.

Whether because of an impulse, or with detailed instruction, all the works begin with a visionary moment that defines what I want to say and how the image will be composed. I am usually drawing at the time, but also may be showering or swimming, as I find water is conducive to creative activity. I try to hold the vision until I can get it down on paper or canvas, as it can be fleeting. The initial vision is then informed, and often inspired, by subsequent research. This research is essential to my work.

Tudor Place is unique because so much detailed information is available about one house. The Peter family, who lived here for 178 years, were proud of their lineage and never threw anything away. Once it became a museum, a professional staff of curators and archivists have continued the family tradition, digging and discovering, preserving and recording, the Tudor Place story. Despite this, there is much to be discovered about the early history of Tudor Place. Images of the house in its earliest period do not exist except William Thornton’s original designs for the house. His “as-built” drawings are not known to exist, perhaps worn out and never copied in those pre-Kinko’s days.

My painting of the original entrance to the property was based on historic maps and other sources, but also on educated guesses. From these sources we know that visitors arrived at Tudor Place from Road Street (R Street today), at the northern end of the property. During the mid-nineteenth century, in accordance with Martha Peter’s will, northern sections of the Peter family’s estate were sold and the main entrance moved to the east side of the property along Congress Street (31st Street today). Information passed down through the family says that slave quarters were located beside the original drive near the entrance, a common arrangement on Southern plantations. The gate posts are conjectural but of a type common in the South at the beginning of the 19th Century. Opportunities for exploring for further evidence of these structures have passed since our neighbors probably would not appreciate major archaeological excavation beneath their properties.

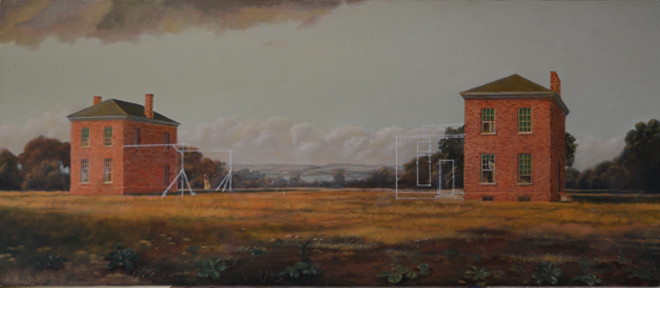

With a house undergoing such close examination as Tudor Place, discoveries are being made constantly. I created a painting depicting the site when it was first purchased by Thomas and Martha Peter in 1805. It was based upon the site’s interpretation at that time. According to the Peter family the previous owners, the Lowndes family, had already constructed the wings of a grand house on the site but got no further. My painting shows the two wings, the east used as stables the west as a dwelling. It also expresses the openness of the site and the distant prospect from Georgetown Heights in those times

Recent scholarship and dendrochronological evidence (the examination of tree rings) indicate that the west hyphen, the section joining the wing to the central part of the house) was built around the same time as the wings, and the east hyphen at a later time. With the results of this examination and the assistance of Curator Grant Quertermous, I am adding the west hyphen to the painting and showing the East Hyphen under construction to take account of the new information. If more information turns up I will change it again, much like a book undergoing revision.

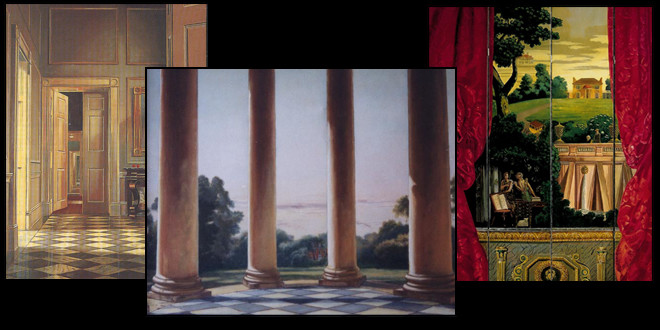

Much of what is important about Tudor Place is subtle. In my painting of the Entry Hall I have tried to convey not just the minute details of the architecture but also the feeling of the space and of the sense of time stood still, and time passed. The artist J.W.M. Turner’s last words were “God is light.” Light is the common subject of all my work. The beauty of the light in Tudor Place is a testimony to the quality of William Thornton’s designs. Being frequently in the house has allowed me the deep examination of the pattern of light and shadow in this space.

Because Tudor Place was lived in by the same family for many generations, the rooms convey layers of history. They tell us a great deal about the taste of the last owner Armistead Peter III (1896-1983). His final iteration of the house was a sort of mid-century modern interpretation of an English country house.

My paintings are constructed realities. I try to find out everything that is known about the subject I am painting. I dread the thought that there is some important detail I have not found. Washington is full of historians, professional and amateur. If I miss something I am sure to hear about it.

The evidence I love most are firsthand accounts from people who were there and saw it as it was. For nineteenth century Washington, Margaret Bayard Smith, wife of Samuel Harrison Smith, editor of the National Intelligencer, is an indispensable source. She seems to have known everyone from President Jefferson on down. She was everywhere and saw everything and recorded the details in her diary. Likewise, we are fortunate that the Peter family recorded the details of their lives, like the arrival of Lafayette at Tudor Place in his yellow carriage in 1824. Britannia W, Kennon Peter in 1895 recorded her remembrances of this event — remembrances I included in my allegorical screen about Tudor Place. [seen in slide show above]:

He drove to Tudor Place in a private carriage. I can see the grand old man now as he entered the door of the parlor, his general manner and dignified appearance making an impression on my mind which time cannot efface. Advancing to my mother, he tenderly embraced her, the meeting with whom no doubt bringing to his mind recollections of former days when he had known her as a child, roving over the lawns of Mt. Vernon, the guest of his everlasting friend George Washington.

—“A Page from the Life of Lafayette: His Visit to the Tudor Place in 1824 Related by the GreatGranddaughter of Mrs. Washington” The Washington Times, July 4, 1895.

Newspapers from the nineteenth century contained masses of detailed description. I had a good technical education and learned architectural drafting. Often buildings are changed over time and I can restore them to the original plans when I need to. From the Tudor Place collection, we can discern the evolution of the architect’s ideas for the house.

The puzzlement of what was here, what it looked like, and how it felt was a constant companion of my childhood, one which has stayed with me and become an integral part of my work as an artist. In my native home in New Zealand such recreations were easy, as European settlement didn’t take place until the middle of the nineteenth century and was much in evidence as were the primeval forests and sites of Maori settlement.

One of the unique things about Tudor Place is that much of it remains as it was from its earliest days. With the exception of the 1876 kitchen addition, the house is little changed architecturally from its completion in 1816. Although many of the contents are still there from Thomas and Martha Peter’s time, other furnishings and the garden are greatly changed. So Tudor Place offers distinct challenges to the history painter— challenges that intrigue me.