#DayOfFacts at Tudor Place

On February 17, 2017, Tudor Place joined hundreds of other museums, historic sites, archives, libraries, science centers and cultural organizations on social media to address confusion over “alternative facts.” This “Day of Facts,” in the words of its grass roots organizers, reaffirmed “values of curiosity, intellectual pursuit and openness. Facts matter, our visitors matter, and we will remain trusted sources of knowledge.”

These are the stories behind the facts shared by Tudor Place:

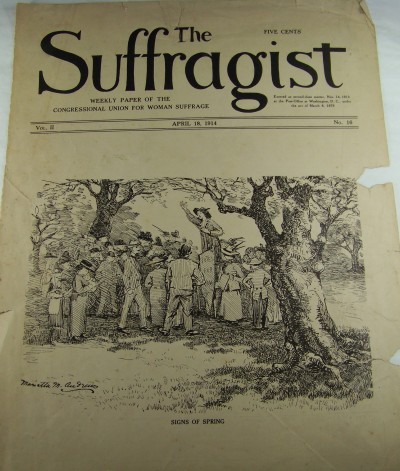

Marietta Minnigerode Andrews: Artist, Poet and Author

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Marietta Minnigerode Andrews (1869-1931) studied art in Washington, New York, Paris, and Munich. In 1895, she married her former art instructor, Eliphalet Fraser Andrews, Director of the Corcoran School of Art. After he died in 1915, she began to write and publish prose and poetry. She was also a founding member of the Washington Watercolor Club, a designer of stained glass windows, and creator of intricate paper silhouettes. This cover drawing for the April 18, 1914, issue of The Suffragist, called “Signs of Spring,” depicts a woman orator addressing a crowd. The Suffragist was published by the National Women’s Party and issued monthly from 1913 until 1921. A group of works by Andrews came to the Tudor Place collection by way of Helen T. Peter, widow of Minnigerode Andrews’s son. Helen married Armistead Peter 3rd, the property’s last private owner, following the death of his first wife, Caroline.

Born in Richmond, Virginia, Marietta Minnigerode Andrews (1869-1931) studied art in Washington, New York, Paris, and Munich. In 1895, she married her former art instructor, Eliphalet Fraser Andrews, Director of the Corcoran School of Art. After he died in 1915, she began to write and publish prose and poetry. She was also a founding member of the Washington Watercolor Club, a designer of stained glass windows, and creator of intricate paper silhouettes. This cover drawing for the April 18, 1914, issue of The Suffragist, called “Signs of Spring,” depicts a woman orator addressing a crowd. The Suffragist was published by the National Women’s Party and issued monthly from 1913 until 1921. A group of works by Andrews came to the Tudor Place collection by way of Helen T. Peter, widow of Minnigerode Andrews’s son. Helen married Armistead Peter 3rd, the property’s last private owner, following the death of his first wife, Caroline.

Max F. Rosinski: “Washington’s Finest Cabinetmaker”

This ca. 1903 Rosinski chair matched a Peter family set once owned by George Washington.

Max F. Rosinski (1868-1962) was born in West Prussia and moved to Washington, D.C., with his family at age 13. On March 12, 1895, he took the U.S. oath of citizenship. After an apprenticeship in cabinetmaking, he established his own shop in the city, where he was active for over 60 years. Tudor Place owner Armistead Peter 3rd was a loyal client, describing him as “the finest cabinet maker that Washington ever had.”

Rosinski’s works at Tudor Place include original pieces like a telephone table and an unusual sideboard/serving table in the Dining Room referencing Colonial style, as well as a pair of chairs commissioned to match the Peter family’s set in the Queen Anne-Chippendale style that were owned by George Washington in the presidential mansion in Philadelphia. Peter also employed Rosinski to repair significant pieces, including the square piano on view in the Saloon, and even had him work on the eight maple doors and pocket doors in house’s reception rooms.

John Luckett: Enslaved by Virginians and Union Soldiers

John Luckett, in characteristic apron and derby hat, with tools on South Lawn.

During the second Battle of Manassas, the Union army sacked a plantation in Lewinsville, Va., in Fairfax County, and “stole” several enslaved people. One of them was John Luckett. Impressed to drive a pair of mules pulling an army supply train, Luckett hatched an escape plan with 20 other men but was one of only three who actually ran. With no pass from an “owner,” Luckett ran the risk of recapture and imprisonment. As he told the story to his first Tudor Place employer, Britannia Peter Kennon, which she then recounted to her grandson, Armistead Peter Jr., Luckett and his fellows were again detained by Union forces but managed to convince them they had been visiting friends. His account of his enslavement and escape ended with, “I just kept on—crossed the Chain bridge and made for Georgetown.”

Kennon described Luckett’s 1862 arrival at Tudor Place in her reminiscences:

John came to ‘Tudor’ in March 1862. I was standing on the brow of the hill by the gate when he came in and asked: ‘Do you want to hire anybody?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I do want to hire somebody!’ ‘Well, I’s looking for a job!’ ‘Where did you come from?’ I asked. ‘Over yonder!’ ‘But, where is ‘over yonder’?’ ‘Over yonder,’ he said. Well, as I wanted some one to work the gardens, I asked him, ‘What wages do you ask?’ ‘Fifty cents a day and you needn’t be afraid to take me neither! Which I told him I was not and from that day to this John has proved to be all that I could wish for.”

Luckett was one of thousands of African-American migrants seeking work then in Georgetown and Washington City. A month after he arrived, Lincoln issued his emancipation decree for the District of Columbia. Did Britannia know he had been enslaved? Perhaps, or perhaps she only realized it later, but she was a single woman running an estate in wartime and needed help. Luckett told her only that he came from “over yonder,” later amended in family lore to “over yonder in Virginie.”

Luckett worked at Tudor Place for 44 years and was loved by the Peter family. His recorded wages in 1904 were $22 a month plus holiday gifts and paid sick leave. “Old John was a character (and one we loved dearly),” wrote one local chronicler, “not much over five feet tall, with grizzled hair and goatee, and always wearing an apron tied around his waist and a derby hat on his head.” Though the Peters offered to buy them a house in Georgetown, Luckett and his wife chose to live across the city. They raised six children in a home on Capitol Hill from which John walked to and from Georgetown every work day, almost until his death in 1906. Family lore maintains that the Peter family adorned his coffin with fronds from their sago palms, a tradition usually observed for family members only.

Margaret Carraher: From a Tiny Pecan, a Mighty Tree

Born in Ireland, cook Maggie Carraher retired from Tudor Place in 1911, the year this was taken.

Margaret, known as “Maggie,” Carraher was an Irish immigrant employed at Tudor Place from 1905 to 1911, when she retired following the death of her employer, Britannia Peter Kennon. Listed on the 1910 census as “cook,” with an immigration date from Ireland of 1868, Carraher was later described by the Kennon’s grandson, Armistead Peter 3rd, who remembered as a small boy “helping” her in the kitchen and “particularly, I used to watch her making bread, which she used to do expertly, and which was the only bread that was used in the house.”

Carraher is perhaps best remembered for a tiny gift she gave Kennon, her mistress: a pecan nut that grew into a tree that today towers more than 80 feet. Britannia planted the nut south of the house. Though pecans’ generally prefer more southern climates, it not only survived but grew so large it had to be relocated, as described in the Tudor Place book by Kennon’s grandson, Armistead Peter 3rd:

The pecan tree to my left was planted during my great-grandmother’s lifetime, in the east end of the arbor, by the kitchen. I think that she had expected it to shade the path in front of the house in the afternoon, but they decided that it was a little too close to the house, and it was then moved down to where you now see it. My Father said that it stayed there for many years, practically with out growing at all, probably as a result of cutting the tap root. However, a few years later it started to grow and ever since then has made a splendid growth every year.

While at Tudor Place, Carraher lived in the room that is now shown as the office and helped care for Britannia Kennon in the last years of her life. She retired at age 62. House records indicated that the next owner, Kennon’s son Armistead Peter Jr., sent her cash gifts at Easter and Christmas for several years after.