The Peter Family’s “Portable Water Closet”

by Rob DeHart

When one looks at human history, the flushing toilet is a relatively new invention. Until the late 19th century, most answered nature’s call by using outdoor privies and latrines. To keep from constantly trekking outdoors, one would use a chamber pot in conjunction with a close stool (a piece of furniture that housed a chamber pot). Then someone would physically empty the contents of the chamber pot into a latrine or cesspool. Not only was this process inconvenient, it was unsanitary, unhealthy, and frankly, pretty smelly.

It is therefore no surprise that generations of inventors devoted a lot of time searching for ways to improve what was commonly known as a “water closet.” Englishman Sir John Harington invented a device in 1596 that looked very much like the modern toilet with a water cistern designed to flush away waste. Scotsman Alexander Cummings improved on this idea in 1775 by patenting the “S” bend beneath the water closet that prevented sewer odors from escaping into rooms.[1] But neither of these inventions were very practical until households could be connected to community water and sewer lines, and this did not begin happening in most cities until the latter half of the 19th century. In rural communities it happened even later.

So the in-between times of the chamber pot and the modern flushing toilet proved to be fertile ground for visionaries searching for an improved bathroom experience. Population growth and changing ideas about hygiene and cleanliness led to dozens of patents being filed between the 1830s and 1870s hoping to alleviate the odors and mess of chamber pots.[2] Some of these patents probably never made it to production, but tucked away in the attic of Tudor Place is one device that did have some success. Its inventor, another Englishman named Robert Wiss, called it a “self-acting portable water closet.” It provides some insight into a time when toilet design was moving toward a more hygienic world.

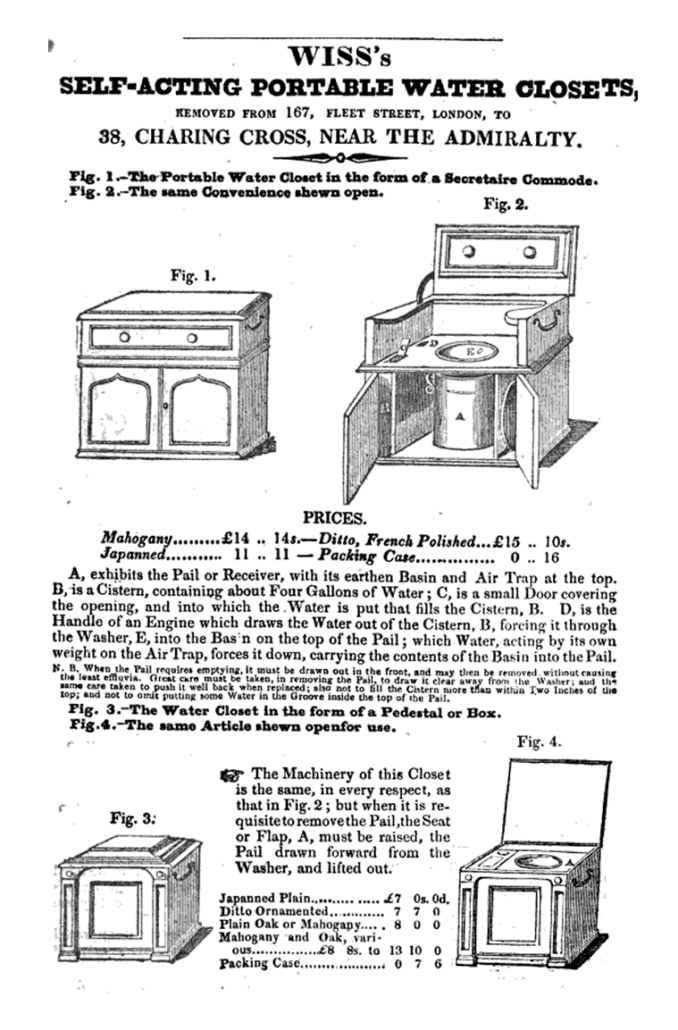

The inner workings of Wiss’s portable water closet are identical to the one at Tudor Place. Image from The Quarterly Literary Advertiser (London), January 1831. Also see a mention of this ad in a blog posted by the USS Constitution Museum at https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/2014/01/18/head-lines/

The first thing one notices when looking at this water closet is that its primary material is mahogany. This would have made it blend in with the typical furnishings of a middle class mid-19th century home. Lifting up the hinged lid exposes another sheet of mahogany, except this piece has a circular cut-out, which essentially served as what we call today a “toilet seat.” Beneath the seat is a blue and white transferware commode bowl that looks much more decorative than just about any toilet bowl made today. To complete the system a galvanized steel pail sits below the bowl to collect waste.

This portable water closet in the Tudor Place collection appears to be based on a design by British inventor Robert Wiss and might date to the 1840s.

The design described thus far is not too different from a common close stool, but Wiss makes it more hygienic by installing a galvanized steel cistern in one side of the cabinet. After the user finished their business, they operated a hand-pump that drew water from the cistern into the commode bowl. The weight of the water in the bowl opened a hinged pan at its bottom that emptied the contents into the pail. In principle it is similar to the workings of a modern toilet. With any luck the excrement washed into the pail where it would be sealed odor-free until it could be emptied.

Robert Wiss manufactured and sold his water closet from the 1830s until at least 1860 through his shop in London and other retailers, but in newspaper ads he routinely complained about “unprincipled imitators” stealing his design.[3] It appears that the water closet in the Tudor Place collection is one of these “imitators” because it displays no markings or patent numbers. The blue and white transferware ceramic commode bowl is very similar to the type used by Robert Wiss and appears English, but lacks his trademark. Everything else about the Tudor Place device is consistent with his design.

A set of brass handles on the cabinet made the device easier to move, thus the word “portable” in its title. But our idea of “portable” is substantially different than it was in the 19th century. While the Peters could theoretically have traveled with this water closet, it would have taken up quite a bit of luggage space. Manufacturers focused on convenience and the respectability attached to having such a device in a household. They also highlighted the need for a portable water closet in case of sickness, suggesting the device could be moved around in a household to provide better bathroom access to an ill family member. During a time when an entire household might have access to just one privy, one can see the advantage of having a commode that could be moved up and down stairs and from room to room.

Yet it is hard to imagine that this water closet worked very effectively. The water pressure provided by the hand pump was probably inadequate to completely empty the bowl, thus creating the same odor problems that came with other close stools. The fact that it is in exceptionally good shape begs the question as to whether it was used much. The only significant damage to the piece is that the hinged pan has broken off of the bottom of the commode bowl, but this could be the result of time and gravity in storage rather than use. Still, indoor plumbing did not come to Tudor Place until the 1870s. So it is easy to imagine the Peter family, with their reputation and resources, investing in such a contraption in an attempt to “modernize” the bathroom situation at their Georgetown mansion.

[1] A good history of all things plumbing-related is sponsored by the Arizona Water Association at www.sewerhistory.org.

[2] M.D. Leggett, Subject-Matter Index of Patents for Inventions Issued by the United States Patent Office from 1790 to 1873, Vol III (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1874), 1664-1665.

[3] Two examples are The Morning Post (London), July 11, 1836 and The Times (London), May 24, 1850. Wiss also claimed that his design was patented, but there is no such record of this in the British index of patents.