Nora Pehrson explains the origins of her essay on Britannia, written while interning here during her senior at Woodrow Wilson High School in Washington, D.C. Nora now attends Colby College in Waterville, Maine.

I was drawn to Britannia’s story because of an abiding interest in women’s history. I wanted to situate Britannia in the broader context of her time. Around the time that Britannia was on the marriage market, the abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights Sarah Grimké wrote “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes,” in which she asserted that the American woman was “a cipher in the nation” because marriage rendered her invisible in the eyes of the law.

I decided to look at how widowhood might have represented a challenge to the cult of domesticity and especially to coverture laws, which took away a woman’s legal rights upon marriage. Although there are no definite answers to the questions that I began with, my research revealed Britannia’s decision to remain a widow allowed her to own and control the estate, which, remarkably, remained in the same family for six generations. Her “tenacity and perseverance,” Armistead Peter 3rd declared, “did as much as anything in the world to preserve this house to the present day.”

Offered through DC Public Schools and taught by the inimitable Cosby Hunt of the Center for Inspired Teaching, Real World History brings together students from across the city to explore a topic of American history in depth and learn what it means to be a historian. After a semester of reading primary sources, conducting oral histories, and making site visits to archives and museums, students go out into the world and serve as interns at various cultural sites throughout DC. During my time at Tudor Place, I did self-guided research and developed my own tour of the house as a docent. Working with the Education Department under the supervision of Laura Brandt was an amazing opportunity to learn how historic house museums operate and, especially, how to make the stories of the house come alive for the public.

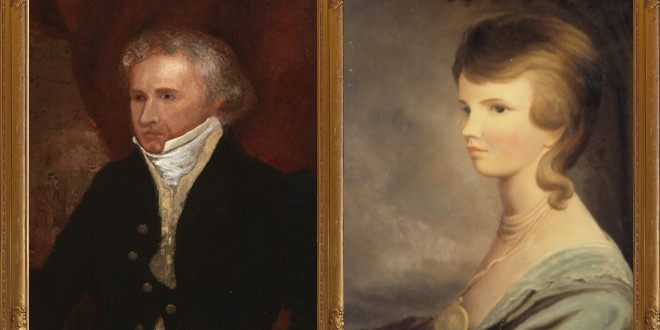

When I arrived at Tudor Place as its first high school intern, I was intrigued by Britannia’s story. Why might she have chosen widowhood over marriage? In a time when the social status of women was so closely connected to the status of their fathers or husbands, why didn’t Britannia remarry? What might her motivations have been? These questions formed the basis of my research project for Tudor Place and the culmination of a year of an extracurricular class called Real World History.

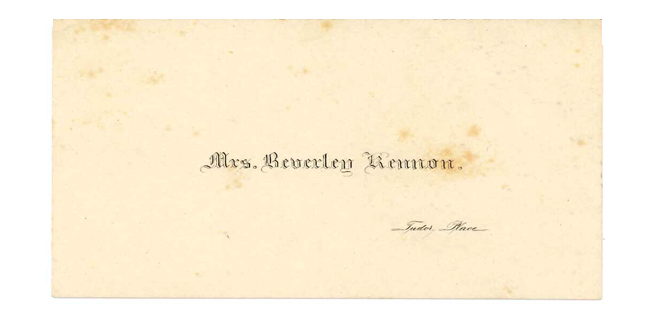

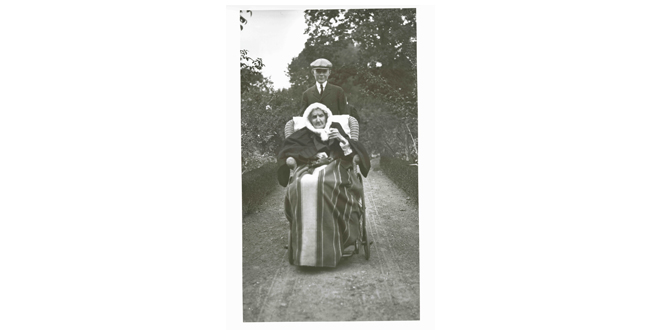

Every visitor who takes a tour of Tudor Place learns the basic outline of Britannia Peter Kennon’s life. Born at Tudor Place in the early years of of the New Republic, Britannia lived for nearly a century. Her decades-long ownership of Tudor Place (from 1854 to 1911) preserved its history and legacy for future generations. Britannia carried out her vision essentially singlehandedly: She was widowed fourteen months into her marriage and never remarried. “Although she had many admirers,” after being widowed in 1844, as her great-grandson Armistead Peter 3rd recalled, she chose to remain single for the rest of her life.