Pencils, Paperclips, and Mystery Objects: Sorting the 20th-Century Desk

|

Armistead Peter, Jr.’s, partner desk: Made by W. K. Cowan Company (Chicago, 1894 to 1916), ca. 1900.

|

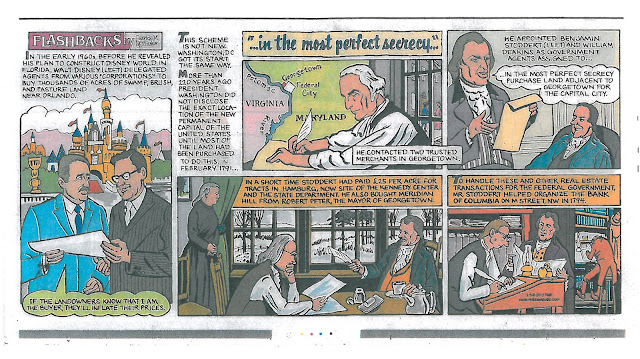

In fall 2012, my internship in collections management focused entirely on the Office — focused, in fact, on a single piece of its furniture, the ca.-1900 Colonial Revival partner desk that anchors the room. The cataloging project required inventorying the contents of the desk, manufactured by W. K. Cowan & Company of Chicago as a replica of George Washington’s presidential desk in New York City. It came to Armistead, Jr., on November 3, 1912, as a gift from his wife, Anna “Nannie” Peter (1872 – 1961).

Sorting through its accumulation of office supplies proved to be a way of sorting through the past century. Like virtually everything in the museum, the desk – down to the interiors of its drawers: pens, pencils, stamps, and stationary supplies – had transferred intact to the Tudor Place Foundation after Armistead 3rd‘s death. Its contents were catalogued then and left undisturbed. For preservation reasons, it recently became necessary to re-house them, and that is where I came in. My internship project was to sort, label, and rehouse the drawers’ contents, photographing, measuring, and cataloguing them in the museum’s PastPerfect digital collections database as I progressed.

Sorting through its accumulation of office supplies proved to be a way of sorting through the past century. Like virtually everything in the museum, the desk – down to the interiors of its drawers: pens, pencils, stamps, and stationary supplies – had transferred intact to the Tudor Place Foundation after Armistead 3rd‘s death. Its contents were catalogued then and left undisturbed. For preservation reasons, it recently became necessary to re-house them, and that is where I came in. My internship project was to sort, label, and rehouse the drawers’ contents, photographing, measuring, and cataloguing them in the museum’s PastPerfect digital collections database as I progressed.

|

| Archival tissue in stacking trays served to hold the desk contents. |

|

| Here is my Collections office work station, located in a former bedroom. |

After three weeks of cataloging, the first drawer was complete. A total of 41 objects, including pencils, dip pens, mechanical pencils, and fountain pens, all made during the first half of the 20th century, had been photographed, catalogued and re-housed, filling four sub-divided trays.

As a curatorial assistant researching WWII-era pencils for an exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, I discovered Bob Truby’s Name Brand Pencils, an entire website devoted to the subject. I learned then that pencils from the Second World War period have distinctive cardboard or plastic ferrules as a wartime adaptation: Metals were needed for the war effort, so hard cardboard or plastic had to substitute for the nickel or brass usually wrapped around the eraser’s base. Although interested to know of this distinction, I was unable to find an example during my Smithsonian tenure.

One year later, in the Armisteads’ desk, I came upon a pencil with a plastic ferrule:

Not everything I found looked familiar, however. The center object in the picture below stumped me at first. On either side are colored pencils “sharpened” by peeling off the wrapped paper. Asking around, I learned from Tudor Place Artist-in-Residence Peter Waddell that the non-writing utensil among them was a tortillon, used by artists to smudge or blend marks.

| Peeling pencils (top and bottom), I recognized. But what was the middle object from the pencil drawer, whose ends peeled away without exposing a writing mechanism? |

| One drawer contained hundreds of unused pen nibs, cloth pen wipes, and eyedroppers for ink and feather quill pens. |

During my fifth week, I found a metal tray full of paper clips. That presented an interesting numbering challenge, as they differ in type and also did not match previous catalogue records. I sorted each type into a separate archival bag to forestall further corrosion and researched the correct name for the contents of each bag. For example, one style, designated a “square clip,” is actually an “ideal” or “triumph” clip according to Early Office Museum, another specialty web site I consulted.

| Paper clips: How to sort and number? |

| By type, of course, and name. |

|

| What’s in your desk? Armistead Peter 3rd’s contained everything from writing implements and sealing wax to drafting tools, photographs, and even a pocket watch.. |

|

| Ephemera and manuscript material from the desk, including these plates, were transferred to the Archive. |

This assortment of rubber stamps also was stored in the desk. Some had deteriorated: For example, the rubber face of one had melted off the wooden handle and adhered to the bottom of the drawer. Others had unidentified surface crystallization.

The stamp collection numbered over 38 items. During my fourteenth week, I finished cataloguing it. While most of the stamps bore predictable labels like “paid”, “received”, and other terms associated with business transactions, one read simply “pigeons.” Armistead Peter, Jr., raised pigeons at Tudor Place, selling them to friends and family. He presumably used this stamp to help organize files pertaining to this hobby.

|

| Manicure set. |

The unique manicure set at right was another unusual find. I initially took it for a pocket knife, but the delicate spoon and pointed blades — for cleaning ears and getting beneath fingernails — ultimately revealed its true function

.