Education to Embassies and its Connection to Agnes Peter

by Sara Law, Archivist

McDonald-Ellis School, c.1900, 27.0217

Massachusetts Avenue is a historic street in Washington D.C. known for being part of the original plans for the city and currently for its world embassies. One embassy, the Embassy of the Philippines sits just east of Scott Circle at the triangular corner of Massachusetts and 17th Street. Before the embassy was built, this corner once housed a school for the daughters of wealthier D.C. residents. A photograph in the Tudor Place Archive with the caption, “McDonald-Ellis School for Girls” reveals the former occupants on this corner as well as its connection to the Peter Family.

By no means the only girls’ school or the first in Washington D.C. for the daughters of the wealthier families of the city, it was an option fairly close to Georgetown. Both a boarding and a day school “one block from the Metropolitan Street Cars and Sixteenth-street Herdic Line” [1], the McDonald-Ellis School for girls was named after its founders Anna Ellis and Lydia McDonald. Born in Ohio, Anna Ellis by 1880 had moved to D.C. and worked as a clerk in the patent office boarding with the family of Lydia P. McDonald [2]. Lydia P. McDonald was born in Indiana and married to the son of ex-senator Joseph Ewing McDonald. When Senator McDonald moved to D.C. in 1875 [3], his son’s family moved to the city as well. After her husband’s death, Lydia with her two children, Joseph and Jessie resided at 1617 N Street with Anna Ellis. As with most girls’ schools at the time, McDonald and Ellis began the McDonald-Ellis School for Girls near their home in 1882 presumably as a source of income. Together, the two women ran the school until Lydia McDonald’s death in 1886.

After McDonald’s death, Anna Ellis took over as caregiver of McDonald’s children and as principal remaining with the McDonald-Ellis school until 1897 when Jessie McDonald, Lydia’s daughter and graduate of the class of 1884, took over as president. The year 1897 was also a notable one for one D.C. resident, Agnes Peter who graduated from the McDonald-Ellis School as valedictorian of her eight-girl class [4].

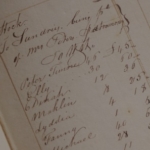

The Evening Star, June 02 1897

The youngest child and only daughter of Dr. Armistead Peter and his wife Martha Kennon Peter, Agnes was born in 1880 and grew up spending most of her life at and around Tudor Place. Because of her status, Agnes was around many other wealthy families who sent their daughters to schools such as McDonald-Ellis. Researching the class lists at the McDonald-Ellis School for Girls’ informational programs from 1882-1891, I realized it was clear there was no Agnes Peter in attendance [5]. However, in a letter from January 1893 from Dr. Peter addressed to the school and his daughter [6], Agnes attended and partially lived at the McDonald-Ellis School from the age of 12 to 17. Apparently, her time at the school was a memorable one, considering Agnes kept the clipping of the school building. After her graduation in 1897, Agnes’ principal Jessie McDonald would step down as president and hand over the school to Reverand Edward R Lewis and Mrs. Rose Baldwin Lewis [7]. They would continue to keep the school open into the beginning of the 20th century.

The Washington Post, 1903

By 1903, the McDonald-Ellis School changed its name and location to the English-Classical School located at 1764 Corcoran Street. Mary Evelyn Steger and Katherine Stockton Hawkins were president and associate president respectively [8]. By 1904, the building at 17th and Massachusetts became the Eastman Misses School run by Anna H Eastman [9]. It served as an educational building for another three decades until the Great Depression where it became a family residence for various people throughout the city. The land was bought by the United States Government in the 1960s and by 1992 [10], it became the home of the Philippine Embassy on the street known affectionately as Embassy Row.

Sources

[1] McDonald-Ellis School for Girls Program, 1889–1890, p. 5. DC MLK Library Research Room.

[2] 1880 D.C. Census. Ancestry.com.

[3] Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. “Joseph E. McDonald.” https://indyencyclopedia.org/joseph-e-mcdonald/

[4] The Times, June 2, 1897, p. 5. Accessed June 12, 2024. Newspapers.com.

[5] McDonald-Ellis School for Girls Program, 1887–1888. DC MLK Library Research Room.

[6] MS 27 Martha Peter Gift Collection, Box 1, Folder 15. “Letter to Agnes Peter care of Miss Ellis at McDonald-Ellis School.” Tudor Place Archives.

[7] Evening Star, October 6, 1899, p. 16. Accessed March 25, 2025. Newspapers.com.

[8] The Washington Post, January 31, 1903, p. 12. Accessed March 31, 2025. Newspapers.com.

[9] Boyd’s Directory of the District of Columbia, 1904. DC History Center.

[10] Embassy of the Republic of the Philippines. https://philippineembassy-dc.org/embassy/

DC Historic Sites. “McDonald-Ellis School.” https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/360