Shovel Ready! Knot Garden Restoration Underway

Having progressed in the past year and a half from imagining to planning to scheduling, restoration of the formal English Knot Garden begins this month! The project entails replacing the garden’s declining English boxwood with hardier varieties, improving the drainage system, and renovating soil beds. This ambitious restoration effort provides an opportunity to deepen our scholarship on the entire landscape feature and expand our commitment to sustainable gardening.

|

| Tobacco blooms. |

Phase one of the project requires: cutting back, digging up, and safely storing the rose bushes; removing the English boxwood, saving those that are still viable; and removing other plants growing within the beds such as the Cleome (common name: “spiderflower”) and flowering tobacco. Next, the soil will be removed down to ten inches and replaced with 3” of sand and fresh topsoil. At the same time, the drainage system will be restored to function effectively. In late October, we will plant new boxwood and replant the roses inside the new edged beds.

|

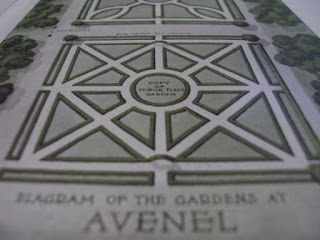

| A copy of our knot garden, diagrammed and planted long ago at Avenel in Virginia, offered insights into our garden’s history. |

|

| This 1984 photo shows the garden shortly after the property passed to the Tudor Place Foundation. |

Over time, more roses were added to the beds. The Knot Garden now holds a multitude of floribundas, hybrid teas, and several antique varieties. The Peters mentioned over 55 different rose varieties in writings that span 150 years. However, when asked in 1982 to write an account of the garden’s evolution, Armistead Peter 3rd admitted he couldn’t identify all the varieties, because they had been replaced so often. In recent years, some have been identified with rosarian Nick Webber while others require further research.

| Roses will be identified and tagged before removal. |

Tudor Place is committed to improving its maintenance program to incorporate more sustainable practices into daily routines. The restoration project presents us with the challenge of maintaining rose beds surrounded by boxwood while using sustainable practices. As our readers may know, rose cultivation can depend heavily on chemicals to control fungal diseases, mites, and a host of other insects. We currently have a spray program that begins in March and ends in October. During spring, we spray the roses twice a week; in early summer up until fall, the schedule stretches to once every three weeks. For many varieties, this program is essential for healthy roses, preventing defoliation by June.

|

| Cleome, or “spiderflower,” leaning in from the left, are among several varieties of flowering plants growing alongside the roses. |

New trials at the New York Botanical Garden and other public sites are testing which rose varieties best tolerate pests without chemical applications, while some public gardens have switched to an all-organic approach. When we reinstall the roses at the end of October, we will apply a new approach to caring for the Knot Garden. First, we will begin reducing the amount of pesticides we apply while monitoring the roses to see which ones can thrive with a less rigorous spraying schedule. We will stop the current spray program completely and replace it with an all-organic spray program. The boxwood hedges surrounding the rose beds will be added to the organic program to reduce the total amount of synthetic chemicals used in the garden.